The English choreographer Matthew Bourne isn’t the first to propose an Oedipal dimension for Swan Lake. Any ballet that old and that popular is fair game for reinterpretation. Stagings over the past 50 years have re-rigged its relationships, condensed the action, and parodied the characters. One version took place on a farm in Minnesota.

The English choreographer Matthew Bourne isn’t the first to propose an Oedipal dimension for Swan Lake. Any ballet that old and that popular is fair game for reinterpretation. Stagings over the past 50 years have re-rigged its relationships, condensed the action, and parodied the characters. One version took place on a farm in Minnesota.

I think the psychologizing began when great stars like Erik Bruhn reworked the ballet to give more attention to the Prince, who traditionally is overshadowed by the ballerina. Siegfried is bored with court protocol and dissatisfied with the prospective fiancées put forth by his mother. The principal dancing is carried by his ideal, the enchanted White Swan, and her heartless Black Swan alter ego, both usually played by the same dancer. Bruhn suggested that Siegfried’s trouble is that he’s in love with his mother, and Bourne expands on this idea, with references to the current British royal family.

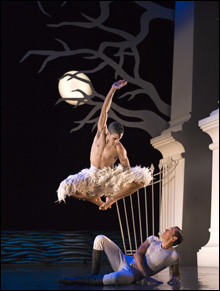

In the Bourne version, which was choreographed in 1995 and given its first Boston performances last week at the Colonial Theatre, the Prince grows up from maladjusted boy to unwilling heir-apparent, a closet homosexual who loves and hates his domineering Queen Mum. He dreams of escaping his royal destiny, squires an ill-mannered commoner, seeks oblivion in a sleazy bar. On the edge of desperation, he sees a vision of the swans. But they’re not ballerinas, they’re bare-chested, hunky men. Siegfried becomes infatuated with the leader and decides to live.

Back home in the palace, his mother is holding one of her ritzy parties and a malevolent Private Secretary is scheming against him. The suave, dangerous Black Swan crashes the party and seduces not the Prince but the Queen. It’s jealousy, not misdirected infatuation, that stings the Prince and precipitates his downfall. A shootout leaves the unfortunate Girlfriend dead, the Black Swan and the Queen in a clinch, and the Private Secretary gloating. Siegfried is pronounced mad and locked in his room, where the swans launch a fatal attack on him and the White Swan.

Swan Lake is frequently treated on a high-critical plane as a moral example — the triumph of pure love and forgiveness over the powers of evil. Both the tragedy and its resolution are realized through the choreography — the serene and æthereal line, balance, and elevation of the white swans pitted against the fiery pointe work of the Black Swan, and the glittering processions and entertainments of the royal court. The characters and their circumstances only make the philosophical drama visible.

ADVERTISEMENT

|

Bourne’s retelling backs off from these old-fashioned æsthetics and focuses instead on the social and political implications of a degenerate monarchy, and the consequences of sexual repression. The whole production is beautifully designed and theatrically satisfying.

Bourne himself isn’t a classically trained dancer, and the only classical scene in his ballet is a parody show-within-a-show — something about butterflies, devils and a dreamy hero in lederhosen. The ensemble performs expertly staged social dances and showy divertissements in Spanish, Italian, and Hungarian styles. The corps of swans leap aggressively and flap their arms, thrusting and twisting their upper bodies. Bourne wants to show the nasty nature of swans, but he doesn’t choreograph the other side of these majestic birds — their gliding elegance and self-composure.

In the central pas de deux, when the Prince should tame the White Swan and gain her trust and love, the dynamics seemed unequal, even reversed, in the performance I saw Friday night. José Tirado, the Swan, dominated Simon Wakefield’s timid Prince throughout this encounter. And when Tirado appeared at the party, a Lothario with a riding whip, the Prince fell apart.

Bourne’s libretto makes sense. The swans are a delusion created in the Prince’s warped imagination. There’s no way they could offer him anything but cruelty and death. The saving beauty of love, as formulated by 19th-century classicism, isn’t available to Bourne’s characters.