EDITOR’S NOTE: Phoenix dance critic Marcia B. Siegel’s Howling Near Heaven: Twyla Tharp and the Reinvention of Modern Dance is now out from St. Martin’s Press. In the following excerpt, Marcia describes the incubation of Deuce Coupe.

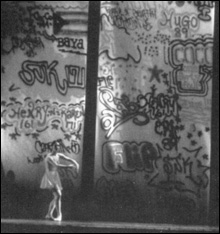

NO JIVE: Eliot Feld’s ballet disappeared quickly, but Deuce Coupe became a landmark.

|

Deuce Coupe was probably the first ballet accompanied by pop records. The Joffrey’s previous scores had included modern composers (Paul Creston, Lou Harrison, David Diamond), contemporary symphonic works with a jazz influence (Morton Gould), third-stream jazz (Kenyon Hopkins, Teo Macero), and the made-to-order rock of Astarte and Trinity. All of these had acceptably artistic dimensions. It was exactly the familiarity of the Beach Boys, their not being art, that was such an asset to Deuce Coupe. In his remarkable book about rock ’n’ roll, Mystery Train, the critic Greil Marcus notes the lack of condescension in certain American pop artists, who have “hoped, no matter how secretly, that their work would lift America to heaven, or drive a stake through its heart.” Marcus was launching a discussion about Randy Newman and the Beach Boys, but he might well have been describing Tharp.

Deuce Coupe became a phenomenal hit, but it had a stressful incubation, right up to its premiere at Chicago’s Auditorium Theater on 8 February 1973. From the start of her discussions with Robert Joffrey, Tharp stipulated that her own company would dance in the work. This would be another first, for even in the legendary 1959 two-company encounter between Martha Graham and George Balanchine, Episodes, the modern dancers appeared in Graham’s dance, the ballet dancers in Balanchine’s with a token crossover dance in each piece (Sallie Wilson in Graham’s dance and Paul Taylor in Balanchine’s). Deuce Coupe was to be a fully integrated production, and this caused anxiety on both sides.

Tharp’s dancers were in awe of the Joffreys’ technical abilities. She broached the idea of the project to them before she took it on. [Isabel] Garcia-Lorca says: “I was not a strong technical dancer, which of course I knew better than anyone else. And being with these ballet dancers was a little daunting. A little scary.” [Kenneth] Rinker felt intimidated too, even though Tharp had already steered him into taking ballet class. He says: “I’m not a ballet dancer and never was and never wanted to be, but I tried to do it like I was.” The prospect of being seen in the City Center Joffrey context was irresistible to the Tharp dancers, though, and Tharp worked out most of the movement on them in her usual way before Joffrey rehearsals began.

Beatriz Rodriguez was among the Joffrey dancers who welcomed the project enthusiastically. She had just come up from the Joffrey II and “I was just open to anything that came along! And it was a wonderful experience with her.” But there was intense resistance from others. The more militant company members resented Tharp’s jazz orientation and the “white” jazz of the Beach Boys. Besides that, she was an unknown, a funky downtown apparition in mismatching clothes, nothing like the star presences who’d come to them before. Once she began work, they felt confused and threatened. Richard Colton had recently joined the main company after two years in Joffrey II. He was understudying several roles in Deuce Coupe so he attended most of the rehearsals. He thought one source of the antagonism was Tharp’s openness. She wasn’t asking the dancers to imitate, to reproduce movement exactly, as they strove to do in their encyclopedic repertory of revivals. “Steps were being thrown out and you as a dancer were taking them and shedding a kind of new light on them. She was excited about mistakes or what things happened, and she was bringing a new breath and life, and a kind of spontaneity. . . . It was a company based on counting. There were no counts. It was just this great music.”

People were grumbling in the dressing rooms: what was this? Tharp assigned Rose Marie Wright to lower the anxiety level. “I became Twyla’s liaison between the dancers and the ballet. Because the Joffrey Ballet people really rebelled against this movement. I mean we went in there and they didn’t know what to make of us. . . . There were dancers that Twyla wanted in the piece, and they didn’t want to be in it. And I’m the one that said, Look, this is really a glissade, this is really an arabesque. . . . I was very exited because she was doing really interesting things with the ballet vocabulary. And it was really challenging to do and I was helping.”