Mark Morris’s L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato is a dance as big as its name, as big as its illustrious associates and enablers, George Frideric Handel, John Milton, William Blake, and a contemporary galaxy of dancers, musicians, and designers. It was the first piece Morris made after his upstart modern dance company took up residence at the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels, in 1988. The Monnaie had been the home of Maurice Béjart, beloved superstar of European choreographers, and the 32-year-old Morris had a lot to prove. Not only that, he had unimaginable resources at his disposal and the smarts to deploy them.

Morris and company lasted three years in Brussels, battling a hostile press and a skeptical public. By the time the idyll came to a close, he had made five smaller but major dances. He finally won over the locals with his flamboyant version of The Nutcracker,The Hard Nut, and returned to America with a solid international reputation under his belt.

First presented in Boston in 1994, L’Allegro returned last weekend (Jan. 20-22) under the combined sponsorship of the Wang Center and the Bank of America Celebrity Series, performed by Mark Morris Dance Group and Emmanuel Music under the direction of Craig Smith, with solo singers Ellen Hargis, Jayne West, Frank Kelle, and James Maddalena.

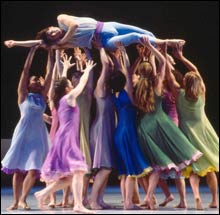

The two-act work is based on Handel’s “pastoral ode,” which in turn was based on Milton’s philosophical dialogue between the light and dark sides of human nature. With the solo singers, chorus, and orchestra in the pit, Morris arranges his 24 dancers in solos, small groups, and ensembles that illustrate the libretto in different ways. Sometimes they seem to experience joy or melancholy; sometimes they act out the events the singers are relating; they make visual puns, trace formal designs, engage in social dances and choreographed seductions. The stage is constantly changing as dancers stream in and out. A terrific scenography of frames, scrims, and light (by Adrianne Lobel and James F. Ingalls) reshapes and colors the space.

You could say all of these things reflect natural life — the moods and temperaments, the times of day, the seasons, the wind. Morris biographer Joan Acocella, in an extraordinary exegesis of the dance, sees it as the cosmos: “everything is there together, and bound together — the universe, the human race, and also the arts.”

I think one reason L’Allegro has been praised so extravagantly is that it doesn’t really reflect the human, natural, or supernatural worlds. It represents them in grandiose terms. If it’s a dance about us, it makes us bigger than we are. No one on the stage simply walks. They walk with a measured step, one hand held out in front of them, the body slanted forward, not breathing, with a horde of identical followers. Or they step down into one foot, and down, and down, the same foot, in endless interweaving chains.

An action always seems to proliferate, even if it’s started by a single gesture. The gesture repeats, the pattern is copied onto another person or another group. People embrace. They roll over their partners and embrace the next person in the circle. The viewer could experience this as signifying universality.

I like L’Allegro best when the compositional patterns evolve. One long sequence at the end of Part I morphs from a throne-room procession to a grand-right-and-left to a mini square dance for six quartets, and on to more inventions that fulfill the poet’s view of an excursion on a sunny day.

I like it least when the dancers pretend to be trees and hunting dogs, or imitate the moon or a fireplace.

Occasionally a word would crystallize out of the gorgeous weave of music, but mostly I couldn’t make out the text. Milton’s high-Renaissance rhetoric (“Hence, loathèd Melancholy,/of Cerberus, and blackest midnight born . . . ,” it begins) scans best on the page. Just the inkling of its noble sentiments makes the dance imposing enough anyway.