BRANDED: The Magnetic Fields may be a band, but the albums are the Stephin Merritt show. |

Stephin Merritt has a cold. “A terrible cold,” he rasps over the phone, though one suspects all colds are terrible in the world of Merritt, the dour, often diffident songwriting brain behind a handful of treasured indie-rock bands including the 6ths, Future Bible Heroes, the Gothic Archies, and, most notably, the Magnetic Fields. “I took some cold medicine,” he explains, “and now all of my m’s sound like b’s.”

Merritt is somewhere in New York. He declines to specify a borough or even reveal whether he’s in the city or, say, upstate in icy Ithaca. His geographic location is not open to discussion: when I ask, “Where am I speaking to you?”, he hesitates before deadpanning, “The phone.”

With a sense of humor as dry as a piece of unbuttered burnt toast, Merritt can be an unpleasant sparring partner. Even under the best of conditions, phone conversations with him are difficult. He tends to pause after each question just long enough that you start to wonder whether he’s contemplating his answer or simply doing his best to suggest that what you’ve asked isn’t worth acknowledging as a question.

The occasion of our conversation is the January 15 release of Distortion (Nonesuch), the first new album from the Magnetic Fields since i (Nonesuch) came out in May of 2004. (The band will support Distortion with two dates at the Somerville Theatre, February 14 and 15.) Not that Merritt hasn’t been busy. Last year, he delivered Showtunes (Nonesuch), a collection of 26 pieces written for several plays directed by Chinese auteur Chen Shi-Zheng. It was his first proper solo album, if you don’t count a 2002 soundtrack for the James Bolton film Eban & Charley (Merge) that’s credited to him. Or, in 2003, the soundtrack for Pieces of April (Nonesuch), a disc that, though also credited to Merritt, features mostly Magnetic Fields tunes.

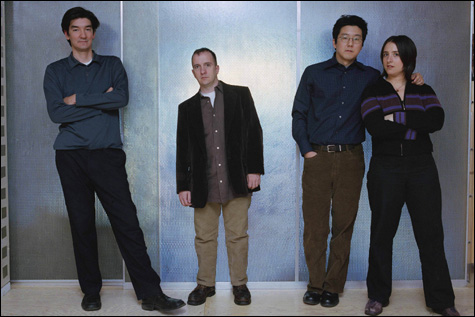

Despite his notoriously grim demeanor, fortune has been smiling on Merritt and the Magnetic Fields for the better part of a decade now. Long before the neo-new-wave synth craze hit and bands like the Killers started mining the ’80s for melodic gold, Merritt was making lo-fi recordings on which electronic textures formed the primary foundation. And as the Magnetic Fields moved from the four-track to the studio, he continued to mix synths in with the organic instrumentation of his own guitar/ukulele, the drumming of Claudia Gonson, the cello of Sam Davol, and the guitar of John Woo. (Live, however, the Magnetic Fields have usually eschewed synths in favor of piano, guitar, drums, and cello; it wasn’t until Merritt and Gonson hooked up with Boston DJ Chris Ewan in Future Bible Heroes that that vintage synths came out in force on stage.)

At the same time, as Merritt began writing songs for others to sing — indie stars like Luna’s Dean Wareham, Sebadoh’s Lou Barlow, and Yo La Tengo’s Georgia Hubley — in a project known as the 6ths, his profile as a pop composer rose steadily until, in 1999, he wowed everyone with the three-disc tour de force 69 Love Songs (Merge), a set that delivers precisely what its title promises. Indeed, the name of Merritt as a songwriter/arranger has come close to eclipsing that of the Magnetic Fields. Which raises the question why not simply stick to the Stephin Merritt brand?