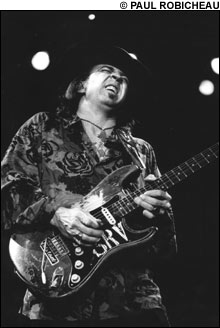

SUPERCHARGED: At its best, Solos, Sessions & Encores offers some worthy blasts from Vaughan’s past. |

Boston is known for the ’60s folk boom, the garage-y “Bosstown sound,” and as one of the birthplaces of alternative rock. But the city was also crucial in the blues revival of the ’80s, when Roomful of Blues and the Fabulous Thunderbirds paved a musical expressway between Boston and Providence in the Northeast, and Austin down south in Texas.New albums by Stevie Ray Vaughan and Ronnie Earl echo back to those days, when Roomful and the Thunderbirds recognized each other as members of the same tribe. Texas’s Thunderbirds and Rhode Island’s Roomful traded gigs and personnel, and shared contacts and friends.

Within that camaraderie, two of the world’s finest guitarists, Austin’s Vaughan and Boston’s Earl, became pals. Earl, who was in Roomful, was introduced to Stevie by his big brother Jimmie Vaughan, the Thunderbirds’ co-founder. They had more in common than a love of blues and their instruments. Both were underdogs. Then unknown, Stevie toiled in Jimmie’s shadow and Ronnie had unenviably replaced Roomful’s beloved Duke Robillard. They also shared a taste for liquor and cocaine. After Vaughan kicked, he supported Earl’s conversion to sobriety.

Their friendship in this world ended on August 27, 1990, when Vaughan perished in a helicopter crash. Without its flamboyant point man, the genre slid back to the fringe. But among those who’ve soldiered on or jumped into the game since, Earl remains a leader, incorporating elements of jazz, rock, and Latin music into his soulful, expressive playing.

Vaughan’s new Solos, Sessions & Encores (Epic/Legacy) would have been a blast from his past 17 years ago. Save for a previously unreleased, undistinguished 1978 studio recording of “You Can Have My Husband” with then-girlfriend singer Lou Ann Barton, this is mostly live teamings of Vaughan with his six-string influences. Although there’s spirited trading with B.B. King and Albert King on “The Sky is Crying” and his star-making turn on David Bowie’s 1983 “Let’s Dance,” three other performances supercharge the disc.

Vaughan contributes teeth-baring pentatonic solos to Lonnie Mack’s “Oreo Cookie Blues” at Atlanta’s Fox Theatre in 1986, a cut likely unissued earlier because Mack bends his Flying V’s strings out of tune during the ferocious sparring. And paired with Jimmie on an ’85 Saturday Night Live, lil’ bro squeezes fireworks into “Change It.” But what’s best is a 1988 New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival punch-out with fellow Texan Albert Collins that’s jacked on howling, shaken notes, and machine-gun riffing.

Earl’s Hope Radio (Stony Plain) is a gentler affair. There’s no better essayist in taste, tone, and tension than this Stratocaster sorcerer, and he’s best live, as caught here playing for a small studio audience at Acton’s Wellspring Sound studio. Earl’s improvisations in the epic “Blues for the Homeless” are sweet and precise. The jazz exploration “Beautiful Child” gets its cool from a graceful blend of octave chords and melody. And his invocations of blues history, like the Hubert Sumlin tribute “Wolf Dance” and “Blues for Otis Rush,” incorporate his own modernist signatures: idiosyncratic bends, staccato repetitions, and twisting scalar runs.

Vaughan carried the blues torch well into the mainstream, and with Hope Radio Earl continues to be a beacon for the style.