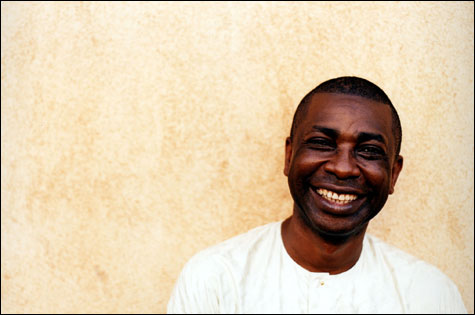

NEW TERRITORY: N’Dour’s latest CD looks for the roots of reggae, blues, and hip-hop in the folklore of the southern Sahara. |

As Senegal’s pre-eminent pop singer, Youssou N’Dour has mastered the art of pleasing diverse audiences. His home-town crowd in Dakar tends to prefer the percussive crack of the mbalax sound that he pioneered in the late ’70s and has continued to tinker with by adding a more modern high-tech sheen. When he’s abroad, N’Dour’s fans are more apt to look to him for roots grooves spun as transcendent high art. As he tells me over the phone from London, “For us, here in the middle, it’s crazy.”

N’Dour has been producing concept albums for the international world-music market ever since the UK’s Folk Roots magazine named him “African Artist of the Century” in 1999. Nothing’s in Vain (2002) was N’Dour stripped down to an acoustic setting; the Grammy-winning Egypt (2004) was a masterful orchestral meditation on Islam. His latest, Rokku Mi Rokka/Give and Take (Nonesuch), looks for the roots of reggae, blues, and hip-hop in the folklore of the southern Sahara. N’Dour and his band, Super Étoile, play the Somerville Theatre on December 10, in a World Music event rescheduled from November 24.

Rokku Mi Rokka isn’t the first disc to source New World black pop genres in the African desert — Baaba Maal and Taj Mahal have done the same. N’Dour, however, homes in on the border region of Senegal, Mali, and Mauritania, the zone where his ears tell him pop music’s most potent DNA lies. American pop has always been part of his mix — he covered the Spinners’ “The Rubberband Man” back in 1985. But when it comes to African roots, his muse has been the propulsive sabar drumming and soaring vocal lyricism of Wolof griots —sub-Saharan sounds. So it’s a welcome surprise to hear him rhapsodizing in the folksy idiom of the nomadic Peul (“Pullo Ardo”), trading verses with the keening, northern voice of Toucouleur singer Ousmane Kange on “Sama Gàmmu,” and veering toward Mauritanian trance music on “Létt Ma,” a story about romance in the desert.

“I cannot say that this is my music,” N’Dour concedes. “But this is the music of West Africa. And when someone plays this music, you don't know anymore whether they are a Senegalese, a Malian, or a Mauritanian. I think there is a very interesting, and very emotional, dialogue going on among these peoples.”

The emotional nexus of N’Dour’s best work has never been located in the high concepts, the production æsthetics, or even the chemistry of his 27-year-old juggernaut of a band. It’s in his near-divine voice, relaxed and cheerful on the patriotic pop ditty “4-4-44,” wailing at the edge of boyish falsetto on the old-school mbalax of “Bàjjan,” or playing the knife edge of agony and ecstasy amid the clapping, ululating, and plucking and chiming of “Baay Faal,” his celebration of Senegal’s Rasta-like Sufi brotherhood.