ARTISTIC LICENTIOUSNESS Mortal Terror is the second installment of Robert Brustein’s trilogy intermingling Shakespeare’s life and work. |

Call it the revenge of Tom Stoppard. Considered a great contemporary playwright by most theater writers, Stoppard has been something of a punching bag to Robert Brustein, one of America's most distinguished critics. Now that Brustein has pretty much left criticism behind in order to concentrate on playwriting, who does his work most evoke? Tom Stoppard.

Of course, anyone tackling a trilogy of plays that intermingled Shakespeare's personal life with his work would rub up against the sparkling screenplay cowritten by Stoppard for Shakespeare in Love, particularly someone as witty, wise — and wise-guyish — as Brustein. If Brustein looks more toward the Borscht Belt and Stoppard to Oxbridge for punning, the similarities are nevertheless ironic, particularly since the first play in the trilogy, The English Channel, could have been titled Shakespeare in Lust.

The object of his desire in that play was Emilia Lanier, increasingly thought to be the dark lady of the sonnets. Mortal Terror, at the Modern Theatre under the auspices of Suffolk University and Boston Playwrights' Theatre (through October 2), takes us to the post-Elizabethan world of King James I, who wants the now-acclaimed playwright to write a — wink-wink — Scottish play justifying the Stuart rule and establishing Jimmy's deep-seeded belief in — nudge-nudge — witchcraft.

Mortal Terror, though, is not an arch mash-up of Macbeth. In fact, Brustein in these first two plays — the third, The Last Will, premieres in New York next year — has come up with a clever way of combining Shakespearean scholarship and Brustein's own thoughts about confronting the abyss, political theater, and the nature of art — particularly questions about where art comes from and the obligations of the artist toward society. And since the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 is brewing in the play's background, it gives Brustein opportunity to make allusions to terrorism and its indebtedness to organized religion.

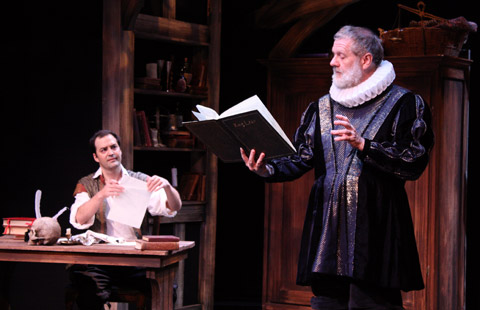

He's helped in those pursuits by a mostly sterling production at the intimately refurbished Modern by several all-stars — director Daniela Varon and actors Michael Hammond (King James), Georgia Lyman (Queen Anne), Jeremiah Kissel (Ben Jonson), and John Kuntz (Guy Fawkes and playwright John Marston). Dafydd ap Rees, who as courtier Sir John Harington challenges Shakespeare to be more than a mouthpiece for the king, may not be as familiar as some of the others, but he's a first-class addition to the local scene, and Christopher James Webb as the plotter Catesby is also a growing presence.

Alas, the odd man out here is Stafford Clark-Price as Shakespeare (he also played him in the New York production of The English Channel). He seems every inch the mere sidekick to the goings-on, playing off the high-class buffoonery of Jonson and Marston, the inanity of the king, the seductions of the queen, and the imprecations of Harington.

Brustein may be trying to make a point about Shakespeare living off his influences, but he's still obliged to make of Shakespeare something other than a charisma-challenged dweeb — albeit a dweeb with genius. Brustein might have allowed himself — to quote Jonson in the play — some artistic licentiousness and at least given Shakes a smooch with Queen Anne before sending him off to make amends with his family in Stratford.

But give Brustein credit. Mortal Terror provides an intriguing window into Will's world that's entertaining, educational, and — I mean this as a compliment even if he sees it as an insult — Stoppardian.